|

|

FinlandFrom Researching Virtual Initiatives in Educationby Merja Sjöblom, Finnish Information Society Development Centre For university-related material see also Finland from Re.ViCa For entities in Finland see Category:Finland

Partners situated in FinlandFinnish Information Society Development Centre Finland in a nutshell(mainly sourced from: Wikipedia) Source: original picture on https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/fi.html Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. The capital city of Finland is Helsinki. The population of Finland is about 5.4 million people, the majority concentrated in the southern region. It is the eighth largest country in Europe in terms of area and the third most sparsely populated country in the Europe. Finland is a parliamentary republic with a central government based in Helsinki and local governments in 336 municipalities. Finland has been a member of the European Union since 1995, independent since 1917 and autonomous since 1809. Finland has two official languages: Finnish and Swedish. Finnish is spoken by 92 % and Swedish by 6 % of the population. The Sami language is an official language in northern Lapland and it is the mother tongue of about 1,700 people. Education in Finland(mainly sourced from: Ministry of Education and the National Board of Education)  Source: origial jpg on: Finnish Education System Finnish education and science policy stresses quality, efficiency, equity and internationalism. It is geared to promote the competitiveness of Finnish welfare society. Sustainable economic development will continue to provide the best basis for assuring the nation's cultural, social and economic welfare. The overall lines of Finnish education and science policy are in line with the EU Lisbon strategy. In Finland, the basic right to education and culture is recorded in the Constitution. Public authorities must secure equal opportunities for every resident in Finland to get education also after compulsory schooling and to develop themselves, irrespective of their financial standing. Legislation provides for compulsory schooling and the right to free pre-primary and basic education. Most other qualifying education is also free for the students, including postgraduate education in universities. Parliament passes legislation concerning education and research and determines the basic lines of education and science policy. The Government and the Ministry of Education and Culture, as part of it, are responsible for preparing and implementing education and science policy. The Ministry of Education and Culture is responsible for education financed from the state budget. The Government adopts a development plan for education and research every four years. The Finnish education system is composed of nine-year basic education (comprehensive school), preceded by one year of voluntary pre-primary education; upper secondary education, comprising vocational and general education; and higher education, provided by universities and polytechnics. Adult education is available at all levels. Schools in Finland(mainly sourced from: Ministry of Education, the National Board of Education and Statistic Finland) Children permanently living in Finland have a statutory right and obligation to complete the comprehensive school syllabus. Nearly all children (99.7%) do this. The principle underlying pre-primary, basic and upper secondary education is to guarantee basic educational security for all, irrespective of their place of residence, language and economic standing. All children have the right to participate in voluntary pre-primary education during the year preceding compulsory schooling. Nearly all 6-year-olds do so. A Finnish child usually starts schooling at the age of seven. The nine-year basic schooling is free for all pupils. Local authorities arrange voluntary morning and afternoon activities for first- and second-year pupils and for special-needs pupils. General upper secondary education commonly takes three years to complete and gives eligibility for polytechnic and university studies. At the end of the upper secondary school students usually take the national matriculation examination. Basic education in a nutshell

See also National Core Curriculum for Basic Education Pre-Primary educationPre-primary education is available free of charge for children one year before they start actual compulsory schooling. Its aim is to develop children's learning skills as part of early childhood education and care. Local authorities have statutory duty to arrange pre-primary education, but for children participation is voluntary and decided by parents. About 96% of the six-year-olds go to pre-primary school. The Ministry of Education recommends that a pre-primary teaching group only include 13 children, but if there is another trained adult in addition to the teacher it may have up to 20 children. Pre-primary instructors have either a kindergarten teacher qualification or a class teacher qualification. Basic educationBasic education is free general education provided for the whole age group. After completing the basic education syllabus young people have finished their compulsory schooling. It does not lead to any qualification but gives eligibility for all upper secondary education and training. Basic education in brief:

Compulsory schooling starts in the year when children turn seven and ends after the basic education syllabus has been completed or after ten years. The post-compulsory levelThe post-compulsory level is divided into general education and initial and further vocational education and training. After basic education, 95.5% of school-leavers continue in additional voluntary basic education (2.5%), in upper secondary schools (54.5%) or in initial vocational education and training (38.5%). General upper secondary educationGeneral upper secondary education usually takes three years and gives eligibility for higher education. About 55% of school-leavers opt for the general upper secondary school. The upper secondary school is based on courses with no specified year-classes and ends in a matriculation examination. It does not qualify for any occupation. After the upper secondary school, students continue in universities, polytechnics or vocational institutions. The admission requirement for general upper secondary education is a school-leaving certificate from basic education. Students apply to general and vocational education in a joint application system. If the number of applicants exceeds the intake, the selection is based on students' school reports. The drop-out rate is low. See statistics: Students in upper secondary general education by region in 2010 Vocational educationThe aim of vocational education and training (VET) is to improve the skills of the work force, to respond to skills needs in the world of work and to support lifelong learning. VET comprises initial vocational training and further and continuing training. The largest fields of vocational education in Finland are Technology and Transport (c. 36%), Business and Administration (19%) and Health and Social Services (17%). The other fields are Tourism, Catering and Home Economics (13%), Culture (7%), Natural Resources (6%) and Leisure and Physical Education (2%). VET is intended both for young people and for adults already active in working life. They can study for vocational qualifications and further and specialist qualifications, or study in further and continuing education without aiming at a qualification. Initial VET

See statistics: Students in curriculum-based basic vocational education numbered 133,800 in 2010 Further and higher education(mainly sourced from: Ministry of Education and Statistics Finland) The Finnish higher education system consists of two complementary sectors: polytechnics and universities. The mission of universities is to conduct scientific research and provide instruction and postgraduate education based on it. Polytechnics train professionals in response to labor market needs and conduct R&D which supports instruction and promotes regional development in particular. The higher education system is being developed as an internationally competitive entity capable of responding flexibly to national and regional needs. Universities in FinlandThe mission of Finnish universities is to conduct scientific research and provide undergraduate and postgraduate education based on it. Universities must promote free research and scientific and artistic education, provide higher education based on research, and educate students to serve their country and humanity. In carrying out this mission, universities must interact with the surrounding society and strengthen the impact of research findings and artistic activities on society. Under the new Universities Act, which was passed by Parliament in June 2009, Finnish universities are independent corporations under public law or foundations under private law (Foundations Act). The universities operate in their new form from 1 January 2010 onwards. Their operations are built on the freedom of education and research and university autonomy. Universities confer Bachelor's and Master's degrees, and postgraduate licentiate and doctoral degrees. Universities work in cooperation with the suspending society and promote the social impact of research findings. There are 16 universities in Finland and the military field which is provided by the National Defence College operating within the Ministry of Defence sector. At universities students can study for lower (Bachelor's) and higher (Master's) degrees and scientific or artistic postgraduate degrees, which are the licentiate and the doctorate. It is also possible to study specialist postgraduate degrees in the medical fields. In the two-cycle degree system students first complete the Bachelor's degree, after which they may go for the higher, Master's degree. As a rule, students are admitted to study for the higher degree. Studies are quantified as credits (ECTS). One year of full-time study corresponds to 60 credits. The extent of the Bachelor's level degree is 180 credits and takes three years. The Master's degree is 120 credits, which means two years of full-time study on top of the lower degree. The system of personal study plans will facilitate the planning of studies and the monitoring of progress in studies and support student guidance and counseling. University postgraduate education aims at a doctoral degree. In addition to the required studies, doctoral students prepare a dissertation, which they defend in public. The requirement for postgraduate studies is a Master's or corresponding degree. Universities select their students independently and entrance examinations are an important part of the selection process. An admitted student may only accept one student place in degree education in a given academic year. Universities also offer fee-charging continuing education and Open University instruction, which do not lead to qualifications but can be included in a undergraduate or postgraduate degree. See statistics: University students numbered 169,400 in 2010 Polytechnics in FinlandThe system of polytechnics is still fairly new in Finland. The first polytechnics started to operate on a trial basis in 1991−1992 and the first were made permanent in 1996. By 2000 all polytechnics were working on a permanent basis. Polytechnics are multi-field regional institutions focusing on contacts with working life and on regional development. There are 25 polytechnics in the Ministry of Education and Culture sector: four are run by local authorities, seven by municipal education consortia and 14 by private organizations. In addition there is the Åland University of Applied Sciences in the self-governing Province of Åland and a Police College subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior. Polytechnics offer

Degree studies give a higher education qualification and practical professional skills. They comprise core and professional studies, elective studies and a final project. All degree studies include practical on-the-job learning. There are no tuition fees in degree education, and the students can apply for financial aid. Polytechnic education is provided in the following fields:

The extent of polytechnic degree studies is generally 210−240 study points (ECTS), which means 3.5 - 4 years of full-time study. This education is arranged as degree programs. The entry requirement is a certificate from an upper secondary school or the matriculation certificate, a vocational qualification or corresponding foreign studies. The requirement for Master's studies in polytechnics is a Bachelors' level polytechnic degree and at least three years of work experience. The polytechnic Master's, which is 60-90 study points and takes 1.5-2 years, is equivalent to a university Master's in the labor market. Each student has a personal study plan, which facilitates student guidance and the monitoring of progress in studies. Polytechnics also arrange adult education and open education geared to maintain and upgrade competencies. The teaching arrangements in adult education are flexible and enable mature students to work alongside their studies. Some 20% of polytechnic students are mature students. See statistics: A total of 21,900 polytechnic degrees were attained in 2010 Education reformThe Finnish education reform is very much based on a top-down comprehensive school. This development started in 1968 and was based on the idea that education has an impact on both well-being of citizens and economic competitiveness. Education reform principles in Finland:

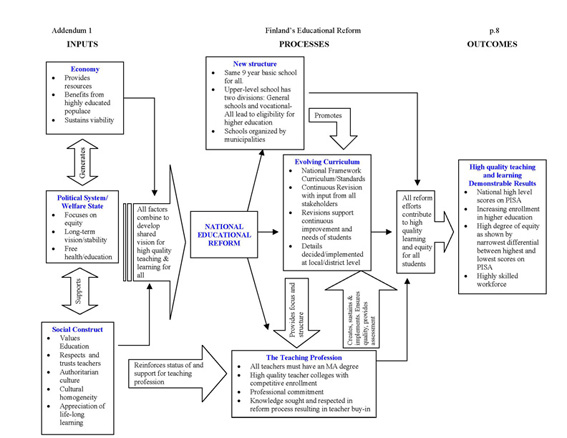

Read a blog entry on this from Bert Maes blog, 2010 Picture of Educational Reform in Finland source: https://www.msu.edu/user/frassine/EAD845%20-%20Educational%20Reform%20in%20Finland.pdf SchoolsA municipal education system was built in the early 1970´s and a nine year compulsory primary school was instituted. With this solution the same education could be provided for all students regardless of their background, economic status, gender or language. Compulsory school is free of charge for all students - there are no costs for education, materials, food or anything else either. There is also a possibility to choose which school to attend to. Teachers in Finland have university-level education. For a permanent teaching position one has to have a master´s degree. Every year only 10 % of applicants who want to become teachers are accepted to Finnish Universities. For teachers there are also plenty of life-long learning opportunities throughout their teaching careers. Further education nowadays is often based on up-to-date researches and cover areas like virtual learning environments, changes in work and effective usage of information technology also from the pedagogic view. Schools have a possibility to plan their own curricula based of course on national core curriculum by the National Board of Education. In the same way schools can choose teaching material and teaching methods independently. Also the testing methods and actual tests are being planned locally by schools or individual teachers. This makes is possible to grade students based on their individual development rather than comparing students with one another. Only in the upper secondary level there is a nationally equal testing system, The Matriculation Examination. Reforms in Finnish Basic Education (source Basic Education Reform in Finland - presentation in 2010)

Administration and finance(mainly sourced from: Ministry of Education and Statistics Finland) In Finland everyone has the right to free basic education, including necessary equipment and text books, school transportation, where needed, and adequate free meals. Post-compulsory education is also free. This means that there are no tuition fees in general and vocational upper secondary education, in polytechnics or in universities. At these levels of education, students pay for their text books, travel and meals. In general and vocational upper secondary education, school meals are free, and students can get subsidy for school travel. In continuing vocational education and in liberal adult education, it is possible to charge modest fees. Those studying in post-compulsory education and training can apply for financial aid. There are special support schemes for mature students See statictics

See pictures in pdf-format

SchoolsThe network of comprehensive schools covers the whole country. The majority of pupils attend medium-sized schools of 300-499 pupils. The smallest schools have fewer than ten pupils and the largest over 900 pupils. Local authorities have a statutory duty to provide education for children of compulsory school age living in their areas. The language of instruction is mostly Finnish or Swedish, but also the Sami, Roma or sign language may be used. Swedish-speaking pupils come to under 6% and Sami-language pupils under 0.1% of all pupils. Upper secondaryGeneral upper secondary education is provided by local authorities, municipal consortia or organizations authorized by the Ministry of Education and Culture. The central government co-finances education with statutory government grants based on student numbers and unit costs per student. The majority of the 435 upper secondary schools in Finland are run by local authorities. Vocational EducationThe Ministry of Education and Culture is responsible for the strategic and normative steering of VET and leads national development. The national objectives of VET, the structure of the qualifications and the core subjects included in them are determined by the government. The details of the qualification and the extent of training are determined by the Ministry of Education and Culture. The authorizations to provide VET are granted by the Ministry. The National Board of Education designs the core curricula and sets the requirements of competence-based qualifications, which describe the aims and key content of the qualifications. Vocational education and training providers are responsible for organizing training in their areas, for matching provision with local labor market needs, and for devising curricula based on the core curricula and requirements. They also decide independently what kind of institutions or units they run. A VET provider may be a local authority, a municipal training consortium, a foundation or other registered association, or a state company. There are around 210 VET providers in Finland. The aim is to develop them to meet according to skills needs. To this end, smaller units will be combined to form local, regional or otherwise strong entities. Quality assurance(mainly sourced from: Ministry of Education and National Board of Education) Education and training providers have a statutory duty to evaluate their own activities and participate in external evaluations. Evaluation is used to collect data in support of education policy decisions and as a background for information- and performance-based steering. Education is evaluated locally, regionally and nationally. Finland also takes part in international reviews, for example PISA Evaluation findings are used in the development of the education system and the core curricula and in practical teaching. They and international comparative data also provide a tool for monitoring the realization of equality and equity in education. Universities and polytechnics evaluate their own education, research and artistic provision and undertake impact analyses. They are assisted by the Finnish Higher Education Evaluation Council (FINHEEC). SchoolsAccording to the Basic Education Act (628/1998), pupil assessment aims at guiding and encouraging studying and developing pupils’ self-assessment skills. Pupil's progress, work skills and behavior are assessed in relation to the objectives of the curriculum. National guidelines and principles for pupil assessment are given in the core curriculum. In the core curriculum pupil assessment is divided into assessment during the course of studies and final assessment. These two have different roles: 1) During the course of studies, the task of assessment is to guide and encourage studying and to help pupils in their learning process. Continuous feedback from the teacher is very important. It should support and guide pupils in a positive manner. With the help of assessment and feedback, teachers guide pupils in becoming aware of their thinking and action, and help pupils to understand what they are learning. Certificates and reports are one way of giving feedback. Pupils are given reports at the end of each school year; in addition, pupils may be given one or more intermediate reports. In the first seven grades of comprehensive school, assessment in reports may be given either verbally or numerically or in a combination of the two. Later assessment must be numerical (scale 4-10), but it may be complemented verbally. 2) The second task of pupil assessment is the final assessment of basic education, on the basis of which pupils will be selected for further studies when they leave comprehensive school. This assessment must be nationally comparable and it must treat pupils equally. The final assessment is based on the objectives of basic education. For the purposes of the final assessment, assessment criteria have been prepared for the grade “good” (8) in all common subjects in the national core curriculum. General upper secondary schoolsAccording to the General Upper Secondary Schools Decree (810/1998), the students and their parents or other guardians are to be provided with information concerning the individual students’ schoolwork and progress of studies at sufficiently frequent intervals. Assessment is based on the objectives defined in the curriculum. The purpose of assessment is to give students feedback on how they have met the objectives of the course and on their progress in that subject. The scale of grades used in numerical assessment is 4–10. Some courses are assessed with passed/failed. At the end of general upper secondary education, students usually take the matriculation examination which consists of at least four tests; one of them, the test in the candidate’s mother tongue, is compulsory for all candidates. The candidate then chooses three other compulsory tests from among the following four tests: the test in the second national language, a foreign language test, the mathematics test, and one test in the general studies battery of tests (sciences and humanities). The candidate may include, in addition, as part of his or her examination, one or more optional tests. The matriculation examination tests are initially checked and assessed by each upper secondary school’s teacher of the subject in question and finally by the Finnish Matriculation Examination Board. The Latin grades and the corresponding points given for the tests are laudatur (praised), eximia cum laude approbatur (passed with exceptional praise), magna cum laude approbatur (passed with much praise), cum laude approbatur (passed with praise), lubenter approbatur (satisfactorily passed), approbatur (passed), and improbatur (failed). Vocational schoolsThe Government decides on the general goals of vocational education and training, the structure of qualifications, and the core subjects. The Ministry of Education decides on the studies and their scope. There are 53 vocational upper secondary qualifications and 119 study programs in them. The curriculum system of vocational education and training consists of the national core curricula, each education provider's locally approved curricula and the students' personal study plans. Assessment is conducted by the teachers and, for on-the-job learning periods and vocational skills demonstrations, the teacher in charge of the period or demonstration together with the on-the-job instructor, workplace instructor appointed by the employer or the demonstration supervisor. The assessment must guide and motivate the students as well as develop their abilities in self-assessment. Finnish Information SocietyFrom 2003 to 2007 The Finnish Government Information Society Programme was acting to improve competitiveness and productivity, to promote social and regional equality and to improve citizens' well-being and quality of life through effective use of information and communications technologies. The Programme consisted of seven sub-sectors:

Work of the The Government Information Society Programme was continued by Ubiquitous Information Society Advisory Board from 2007 to 2011. The Board had around 40 members from the involved Ministries, public administration, NGOs and business life. The Advisory Board aimed to transform Finland into an internationally recognized, competitive, competence-based service society with a human touch. The Advisory Board had the duty to:

Read the action plan of Ubiquitous Information Society Advisory Board in pdf-format: http://www.arjentietoyhteiskunta.fi/files/73/Esite_englanniksi.pdf or open a PowerPoint slideshow http://www.arjentietoyhteiskunta.fi/files/29/National_Information_Society_Policy_in_short.ppt The Advisory Board worked in six working groups to fulfill its aims:

StatisticsFor a number of years Statistics Finland has been describing evolvement of the information society in Finland. Compilations have been published on the topic and annual statistics are produced on the use of information and communications technology. There are for example following statistics: Finnish Information Society 2020source: Sitra, the Finnish Innovation Fund The following vision of the Finnish information society was developed in collaboration with the Ministry of Transport and Communications as a contribution to the information society strategy process. Discussion on the vision continues.

ICT in education initiatives

Virtual initiatives in schoolsVirtual education projects in hospital schools eSKO is a project in Finland concentrating to develop virtual education in hospitals. The project is funded by the National Board of Education and the municipality of Masku. LUMI is a similar project for sick students of Rantavitikka Comperehensive School, funded also by the NBE. AntiVirus is also funded by the NBE, coordinated by Viikki Teacher Training School of Helsinki University and partnering with Teacher Training School of Jyväskylä. All these projects aim to organize and develop virtual education for sick students, especially those who suffer from long-term deceases, not being able to attend school. Virtual education is an opportunity to offer the student means to maintain social connections to his or hers friends, class and school as well as to improve cooperation between home and school. This way the student also has a better change to interaction and studying with his or hers own class. Studying is not dependent on the place where the student is. eSKO http://sairaanakinselviaakoulusta.wordpress.com/, LUMI http://lumihanke.blogspot.fi/ and Antivirus http://antivirushanke.blogspot.fi/ project web pages are available in Finnish. Coordination project for distance learning, City of Turku Coordination project for distance learning aims to collect and spread good practices of distance learning, collaborate with different distance learning projects, developers and creators, form new kinds of networks and create new operation models to support different distance learning needs. The project also does research on how different learning materials suit distance learning and distribute data nationally and to the extent appropriate internationally. In this project distance learning is defined as ICT supported learning, where student and teacher are physically in different places. Distance learning can be a part of other education (multiform education). Interaction can be simultaneous or happen at different times. The project covers all general education and collects also good practices from vocational education and basic education of arts. Within the project together with the University of Turku nationally valid reports on distance learning solutions are obtained. The project started in September 2010 and continues until the end of 2012. It is mainly financed by the National Board of Education and coordinated by educational system of City of Turku. The project web pages http://etaopetus.wordpress.com/ are available in Finnish. Virta - virtual regional resources - a project in Tampere region Virta project is a development project for learning environments. The project aim is to create a regional model for virtual classes, using web conference solutions. These solutions are especially targeted to secure equal opportunities for small groups to learn mother tongue and religion. During the school year 2011-2012 subjects are Arabic, Somali and Russian as mother tongue, German as A2 language and Islam and catholic religions. The model can also be used in other education, such as optional subjects or preparatory education. Fourteen schools from Tampere region are participating in this project. The project started in 2008 and continues to the end of 2012. It is financed by the National Board of Education and the City of Tampere. Virta project´s web pages http://koulut.tampere.fi/hankkeet/virta/index.html are available in Finnish. ENO-Environment Online ENO is a global virtual school and network for sustainable development and environmental awareness. Environmental themes are studied within a school year on a weekly basis. Thousands of schools from 124 countries have taken part. The ENO programme has been running since 2000. It is coordinated by ENO Association based in the city of Joensuu, Finland. ENO has received funding from the National Board Of Education and municipalities in the Joensuu region. ENO web pages http://eno.joensuu.fi/basics/briefly.htm Virtual schools in Finland: Kulkuri (”Tramp”) is a distance school for Finnish children living abroad. In the distance school they study together with students from other counties. The main subject is Finnish language, but if needed, students can complete the whole comprehensive school syllabus. Kulkuri´s web pages http://www.peda.net/veraja/kulkuri are available in Finnish. Verkkoperuskoulu (Virtual comprehensive school) is a comprehensive school for adults, young people who no longer belong to the compulsory education age group and for people that cannot study full time. The school web pages http://www.lahdenkansanopisto.fi/fi/opintolinjat/peruskoulu/verkkoperuskoulu are available in Finnish. Nettiperuskoulu is a distance learning school maintained by Otava Folk High School. Its purpose is to offer a possibility to accomplish basic education curriculum that for some reason has not yet been completed. Main target group are adults and younger people, who are beyond compulsory education age group and do not have a graduation certificate from basic education. The school web pages http://www.nettiperuskoulu.fi/fi/sisalto/01_etusivu are available in Finnish. Virtual initiatives in post-secondary educationThere are at least 76 upper secondary schools in Finland that arrange distance learning. Many of them work closely together with local vocational schools. The vocational and upper secondary schools offering distance learning also form networks with each other. One upper secondary or vocational school can also be a partner in several distance schooling networks. Distance learning networks (most links contain information only in Finnish)

Helsinki Virtual campus creates an environment to good learning Virtual campus is a new, innovative concept for upper secondary and vocational education in Helsinki. Phenomenon based learning has a key role in this concept. All upper secondary and vocational schools in Helsinki are developing the new virtual campus concept - which makes it possible to offer wider course selections and new ways of learning for students. The concept also makes is possible for students to study virtually even thru the whole school. The new campus concept starts from the beginning of school year 2013-2014. Innovative, creative and collaborative learning is the basic idea, emphasizing learning processes of students (instead of the traditional teaching processes). As development methods are competence based curriculum, phenomenon based learning, virtual portfolios, learning platforms and social media. Tools used can be for example eMaterials, wikis, blogs and other social media tools. Read more in Finnish from: https://sites.google.com/site/stadinekampus/home, http://www.maakuva.fi/stadin-ekampus-vie-lukion-verkkoon/ and http://helsinginopetusvirasto.wordpress.com/2012/05/04/lukiokampukset-tulevat-mika-muuttuu/

Asiantuntijaverkosto (Network of experts) allows specialists from different trades of industry and business, NGO's, politics and universities contribute to learning. Experts bring practical experience to theory-based lectures in upper secondary schools. Experts participate in classes using web conference technology. The system is easy to use and the visit does not require much preparation neither of the teacher nor the expert. This is also an economical and ecological way to transfer know-how. Games and virtual worlds to support education OVI project is short for “Learning games and virtual world solutions supporting the quality and reforming of education”. The project aim is to promote virtual learning environments, especially virtual worlds, and games as learning solutions towards pedagogically meaningful education. The project is financed by the National Board of Education. The OVI project web pages http://www.peda.net/veraja/konnevesi/lukio/ophhanke2010 are available only in Finnish. Lessons learntWithin the VISCED project has been defined categories for different levels of virtual schooling:

General lessonsNotable practicesReferences

Relevant websites

|